Sacred Texts Native American California Index Previous Next

THE mythology of the Indians of California goes back much farther than our mythology: it goes back to the time of the FIRST PEOPLE--curious beings who inhabited the country for a long period before man was created.

The myths of the Mewan tribes abound in magic, and many of them suggest a moral. They tell of the doings of the FIRST PEOPLE--of their search for fire; of their hunting exploits; of their adventures, including battles with giants and miraculous escapes from death; of their personal attributes, including selfishness and jealousy and their consequences; of the creation of Indian people by a divinity called Coyote-man; and finally of the transformation of the FIRST PEOPLE into animals and other objects of nature.

Some explain the origin of thunder, lightning, the rainbow, and other natural phenomena; some tell of a flood, when only the tops of the highest mountains broke the waves; others of a cheerless period of cold and darkness before the acquisition of the coveted heat and light-giving substance, which finally was stolen and brought home to the people.

The more important features of Mewan Mythology may be summarized as follows:

The existence of a FIRST PEOPLE, beings who differed materially from the present Indians, and who, immediately before the present Indians were created, were transformed into animals, trees, rocks, and in some cases into stars and other celestial bodies or forces--for even Sah'-win-ne the Hail, and Nuk'-kah the Rain were FIRST PEOPLE.

The preëxistence of Coyote-man, the Creator, a divinity of unknown origin and fabulous 'magic,' whose influence was always for good. 1

The existence (in some cases preëxistence) of other divinities, notably Wek'-wek the Falcon, grandson and companion of Coyote-man, Mol'-luk the Condor, father of Wek'-wek, and Pe-tā'-le the Lizard, who, according to several tribes, assisted Coyote-man in the creation of Indian people.

The possession of supernatural powers or magic by Coyote-man, Wek'-wek, and others of the early divinities, enabling them to perform miracles.

The prevalence of universal darkness, which in the beginning overspread the world and continued for a very long period.

The existence at a great distance of a primordial heat and light giving substance indifferently called fire, sun, or morning--for in the early myths these were considered identical or at least interconvertible. 2

The presence of a keeper or guardian of the fire, it being

foreseen by its first possessors that because of its priceless value efforts would be made to steal it.

The theft of fire, which in all cases was stolen from people or divinities living at a great distance.

The preservation of the stolen fire by implanting it in the oo'-noo or buckeye tree, where it was and still is, accessible to all.

The power of certain personages or divinities--as Ke'-lok the North Giant, Sah'-te the Weasel-man, and O-wah'-to the Big-headed Lizard--to use fire as a weapon by sending it to pursue and overwhelm their enemies.

The conception of the sky as a dome-shaped canopy resting on the earth and perforated, on the sides corresponding to the cardinal points, with four holes which are continually opening and closing. A fifth hole, in the center of the sky, directly overhead, is spoken of by some tribes.

The existence, at or near the north hole in the sky, of Thunder Mountain, a place of excessive cold.

The presence of people on top of or beyond the sky.

The presence of people on the underside of the earth. (This belief may not be held by all the tribes.)

The existence of Rock Giants, who dwelt in caves and carried off and devoured people.

The tendency of the dead to rise and return to life on the third or fourth day after death.

The prevention of the rising of the dead and their return to life by Meadowlark-man, who would not permit immortality.

The creation of real people, the ancestors of the present Indians, by the transformation of feathers, sticks, or clay. 3 Of these beliefs, origin from feathers is the most distinctive

and widespread, reaching from Fresno Creek north to Clear Lake. 4

The completion and perfection of newly created man by the gift of five fingers from Pe-tā'-le the Lizard-man, who, having five himself, understood their value.

In addition to the more fundamental elements of Mewan Mythology there are numerous beliefs which, while equally widespread, vary with the tribe and are of less importance. Among these are the tales of the elderberry tree--the source of music and other beneficent gifts to the people. In the beginning of the world the elderberry tree, as it swayed to and fro in the breeze, made sweet music for the Star-maidens and kept them from falling asleep; its wood served Tol'-le-loo for a flute when he put the Valley People to sleep so that he might steal the fire; and today it serves for flutes and clapper-sticks in nearly all the tribes and plays a vital part in their ceremonial observances.

Other widespread beliefs are that the great hunters of the FIRST PEOPLE were the Raven, Cougar, and Gray Fox; that Mermaids or Water-women, who sometimes harm people, dwell in the ocean

and in certain rivers; that the echo is the Lizard-man talking back; that certain divinities have the magic power of accomplishing their desires by wishing; and that the red parts of birds--as the chin of the Humming-bird, the underside of the wings and tail of the western Flicker, the breast of the Robin, and the red head of the Mountain Tanager and certain others, indicate that these parts have been in contact with the fire.

There are also numerous local beliefs, confined to particular tribes or groups of tribes. Thus the Inneko tribes, those living north of San Francisco Bay, tell of a flood; the two coast tribes say that in the beginning the Divinity Coyote-man came to America from the west by crossing the Pacific Ocean on a raft; the Northern Mewuk believe that they came from the Cougar-man and Grizzly Bear-woman; the Tu'-le-yo'-me say that when Sah'-te set the world on fire, Coyote-man made the flood and put out the fire. Other local myths are that Wek'-wek was born of a rock; that Chā'-ke the Tule-wren, a poor despised orphan boy, shot out the sun, leaving the world in total darkness; that His'-sik the Skunk, whose greed and oppression were intolerable, was destroyed by the superior cunning of Too'-wik the Badger; that He'-koo-lās the Sun-woman owed her brilliancy to a coat of resplendent abalone shells; that the We'-ke-wil'-lah brothers, tiny Shrews, stole the fire from Kah'-kah-te

the Crow and by touching a bug to the spark made the first firefly. Numerous others will be found in the tales--in fact every tribe has myths of its own. Furthermore, in the general mythologies, each band or subtribe has slight variants, so that even the creation myths, as related by different bands, present minor differences.

The repeated mention in the mythologies of certain objects and practices (as the ceremonial roundhouse, the use of the stone mortar and pestle for grinding acorns, the use of baskets for cooking, the use of the bow and arrow and sling in hunting, the practice of gambling by means of the hand-game, and many others) proves that these objects and observances are not of recent introduction but were among the early possessions and practices of the Mewan tribes.

It is important to discriminate between the real mythology of a people, the tales that deal with personages and events of the very remote past, and present day myths, which deal with happenings of the hour or of the very recent past. Some of the present day myths of the Mewan tribes may be found in a separate chapter at the end of the volume.

The names of individual personages among the FIRST PEOPLE were carried on to the animals, objects, or forces which these people became at the

time of their final transformation, and are still borne by them. Hence in the accompanying stories the names of the various animals and objects should not be understood as referring to them as they exist today but to their remote ancestors among the FIRST PEOPLE. Whatever their original form--and the Indian conception seems to picture them as half human--the distinctive attributes of the FIRST PEOPLE were in the main handed down to the animals and objects they finally became.

Thus Oo-soom'-ma-te's fondness for acorns was not diminished by her transformation into the Grizzly Bear; Yu'-wel's skill as a hunter did not forsake him when he turned into the Gray Fox; He-le'-jah's prowess as a deer slayer lost nothing when he changed to the Cougar; and Too'-pe's nocturnal ways were not abandoned when she became the Kangaroo Rat. Similarly, Ko-to'-lah's habit of jumping into the water is perpetuated by the Frog; Too'-wek's preëminence as a digger is still conspicuous in the Badger; To-to'-ka-no's loud penetrating voice is even now a signal characteristic of the Sandhill Crane; while the swiftness of flight of Wek'-wek, Hoo-loo'-e, and Le'-che-che who could shoot through the holes in the sky, ever opening and closing with lightning rapidity, are today marked attributes of the Falcon, Dove, and Humming-bird. So it is also with Nuk'-kah the Shower and Sah'-win-ne the Hail, who were sent to overtake and capture a fleeing enemy and who

to this day are noted for the velocity and force of their movements. Such cases might be multiplied almost indefinitely.

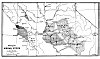

The territory of the Mewan tribes comprised the lower slopes and foothills of the Sierra Nevada between the Cosumnes River on the north and Fresno Creek on the south, with the adjacent plain from the foothills to Suisun Bay, and also two smaller disconnected areas north of San Francisco Bay--one in the interior, reaching from Pope Valley to the south end of Clear Lake, the other on the coast, from Golden Gate northerly nearly to the mouth of Russian River. (See accompanying map.)

At present the vanishing remnants of the Mewuk tribes are scattered over their old territory on the west flank of the Sierra; the handful that remain of the Tuleyome tribe are gathered in a small rancheria on Putah Creek in Lake County; while the sole survivors of the Hookooeko and Olamentko tribes (in each case a single person) still cling to their original homes on Tomales and Bodega Bays.

The California tribes are stationary, not nomadic; they have lived for thousands of years in the places they now occupy, or did occupy until driven

Click to enlarge

Distribution of the Mewan Stock

away by the whites; and during this long period of isolation they have evolved different languages for even among tribes of the same linguistic group the differences in language are often so great that members of one tribe cannot understand the speech of another. 6

As the languages of the tribes composing the Mewan stock show varying degrees of kinship, so their myths exhibit varying relationships. Those of the Sierra region are the most closely interrelated; those of the San Francisco Bay region and northward the most divergent.

18:1 Partial exceptions, doubtless a result of contact with neighboring stocks, occur in two tribes: the Wi'-pa say that Coyote-man boasted beyond his powers; and the Northern Mewuk say that he was selfish.

18:2 A partial exception is the belief of the Hoo-koo-e-ko of Tomales Bay who say that in the beginning the source of light was He'-koo-las the Sun-woman, whose body was covered with shining abalone shells.

19:3 A single exception has been found: The Northern Mewuk account for people by the gradual evolution of the offspring of the Cougar-man and his wives, the Grizzly Bear-woman and the Raccoon-woman.

20:4 The widespread belief in the origin of people from feathers accounts for the reverence shown feathers by some of the tribes. This feeling sometimes manifests itself in a great fear or dread lest the failure to show proper respect for feathers, or to observe punctiliously certain prescribed acts in connection with the use of feather articles on ceremonious occasions, be followed by illness or disaster. This awe of feathers, I have observed among the Hoo'-koo-e'-ko of Tomales Bay, the Tu'-le-yo'-me of Lake County, and the Northern Mewuk of Calaveras County.

24:5 For a detailed account of the distribution of these tribes see my article entitled, "Distribution and Classification of the Mewan stock of California," American Anthropologist, vol. ix, 338-357.

27:6 Hence in the accompanying myths the name of the same personage or animal differs according to the tribe speaking. Thus Coyote-man may be Ah-hā'-le, Os-sā'-le, O-lā'-choo, O-lā'-nah, O-let'-te, Ol'-le, or O'-ye. Similarly, the Humming-bird may be Koo-loo'-loo, Koo-loo'-pe, or Le'-che-che. The Falcon or Duck-hawk, on the other hand, is Wek'-wek in all the tribes. This is because his name is derived from his cry. Many other Indian names of mammals and birds have a similar origin.